It’s the end of the month. Rent is due, bills are looming and the peanut butter in the cupboard is looking lonely all on its own. It can be stressful even if you have a regular income.

But, what is a regular income these days? What if your job is precarious or you’re not getting on with your boss? What if you’re self-employed and the phone isn’t ringing? What if your mental health is suffering and you can’t take those shifts? What if you’re on benefits and the government decides – again – to tighten things up, to introduce more barriers, like the ones that made I, Daniel Blake, such a truthful and painful watch? What happens then?

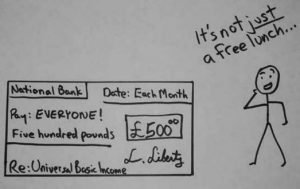

What if we all benefited from a Universal Basic Income? How would that change things? Universal Basic Income, or UBI, does pretty much what it says on the tin. It is a guaranteed income that everyone receives unconditionally, from cradle to grave. It ensures that no one falls below the poverty line. Rich folk might not rely on their UBI as much as others, but they still get it. With UBI, we’re really all in it together.

UBI has hit the headlines recently. A number of pilot projects in Canada, the USA, Finland, Brazil, India and elsewhere have garnered media attention, and have provided encouraging results. UBI has been in the Green Party manifesto for years, and it had a mention in the Labour Party’s recent election manifesto. And, most encouragingly, US Democrat leadership candidate, Andrew Yang, has made UBI the central policy in his bid to win his party’s nomination and oust Trump. Yang’s ‘Freedom Dividend’ has catapulted him from being an afterthought to a dark horse contender.

Arguments for UBI vary. Some emphasise the benefits of lifting people out of poverty and eliminating the stigma associated with benefits. Others stress how UBI could herald a new and much-needed social contract between individuals and the state. The potential boost to entrepreneurialism, the arts and volunteering are also heralded, as UBI would allow people to chase their career ambitions, unfettered by concerns about income. Want to write the next Harry Potter? Go for it! Still others suggest that, with automation threatening millions of jobs, UBI is simply an inevitability.

Although these reasons are all valid, I believe there is another rationale that hasn’t been discussed: mental health. As a health historian, I have the luxury of taking in the ‘long view’ when it comes to mental health. During the last 120 years or so (since 1900), something rather alarming becomes apparent. Between 1900 and about 1980, there was a real focus on preventing mental illness. Since 1980, the focus has primarily been on treatment. So, why does this matter and how does it relate to UBI?

Preventing Mental Illness

First of all, let me explain what I mean by ‘prevention’, which can be a loaded term. I’m not talking about preventing people from being who they are, or using eugenic approaches to root out ‘undesirables’. I’m also aware that some would argue that there is nothing to prevent, that we should be encouraging more variety of human experience, rather than less, and that we should make society more accommodating for those who are different. As a supporter of neurodiversity, I couldn’t agree more (and UBI could be a tool in doing this – see below).

To me, preventing mental illness is rooted in a simple axiom: mental illness can be caused, triggered or exacerbated by socio–economic problems. Therefore, if we’re serious about reducing both the amount of mental illness and its impact, we must consider bold policies that tackle these problems.

For most of the twentieth century, people knew this and, what’s more, did something about it. Underlying the child guidance and mental hygiene movements of the first half of the twentieth century was the idea that, in order to prevent mental illness, it was necessary to instil social changes. While we might not agree with the paternalistic and moralistic approach taken up by some involved in these movements, it’s hard to quibble with their concerns about the impact of poverty, violence and chaotic living conditions on mental health.

Following WWII, efforts were increased to understand the link between environmental factors and mental health, leading to a new discipline called ‘social psychiatry’. Social psychiatry was explicitly preventive and relied on the social sciences to help explain the origins of mental illness. In the USA, the newly-formed National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) began funding social psychiatry research, yielding fascinating results.

The first conclusion made by social psychiatrists was not a big surprise: people living in poverty had higher rates of mental illness than their wealthier counterparts. Why was this the case? One answer can be found in research emerging at roughly the same time on the role of stress in human physiology. People living in impoverished, chaotic and often violent settings experienced higher levels of stress which, in turn, triggered the release of certain hormones in the brain.

Today, researchers are exploring the role of inflammation – an ancient medical concept ‒ in these stress reactions. Putting physiology to one side, we can all think of other reasons why poverty might create poor mental health and prevent people with mental illness experiencing – improvements in their health.

The second insight was less of a surprise than a dirty secret laid bare: inequality. Opening their book on the subject, August Hollingshead and Fritz Redlich declared that: ‘Americans prefer to ignore the two facts of life studied in this book: social class and mental illness.’ Focussing on the small city of New Haven, Connecticut, Hollingshead and Redlich discovered that members of the lowest strata of New Haven’s entrenched class system were far more likely to experience serious mental health problems and far less likely to receive adequate care.

Inequality is more than just poverty; it also encompasses lack of opportunity, class bias, disenfranchisement, damaged self-worth and – often ‒ racism. Inequality results in hopelessness that can both trigger depression, anxiety, addictions and other diseases of despair.

If the first two findings made by social psychiatrists were not particularly surprising, the final one was – in a way at least. After WWII, many researchers were convinced that crowded urban living could cause mental illness, basing some of their theories on NIMH-funded rat experiments. But the results of a large study of Manhattan residents contradicted this assumption. New Yorkers were not suffering from overcrowding, the researchers argued. In contrast, they were suffering from the opposite: social isolation.

As with poverty and inequality, it doesn’t take much to understand why social isolation is bad for mental health. We all need to be loved and to give love. Alone time can be great, but being lonely with no one to talk to can make life seem bleak and purposeless.

UBI and Mental Health

So how might UBI address poverty, inequality and isolation and, in turn, prevent mental illness? This might seem self-evident, but it’s worth articulating.

First, UBI is designed to take people out of poverty. It also allows people – mainly women – stuck in abusive relationships the financial means to escape. Given that abuse is also a major factor in developing mental illness, UBI could also provide a preventive function in this way.

The guaranteed nature of UBI could also do wonders for the welfare system. These days, the welfare system is essentially a financial gatekeeping service. It sorts out the deserving from the undeserving, establishing an intricate maze through which people must navigate. People working in this system are not really there to help others, but rather to prevent them from accessing benefits.

The sad thing is that most people working in the welfare system want to help others. If welfare workers didn’t have to spend their time gatekeeping, they could get to work on the really intractable problems, such as mental illness, addictions and helping people determine what they want to do with their lives. I would have loved to have been able to do these sorts of things when I worked as a youth counsellor in Canada. What did I do? You guessed it: I served as a benefits gatekeeper.

Second, UBI would facilitate upward mobility – and, therefore, reduce inequality ‒ by giving people an income while they went back to school, started their own business, embarked upon artistic ventures or changed careers. It would reduce the hopelessness and shame associated with deprivation and, in so doing, prevent those diseases of despair. As it is given to everyone, parents, carers, volunteers and others currently doing unpaid work in society would also benefit, signifying the tremendous value in the work that they do.

Finally, UBI could foster social inclusion in society. It would give people the means to direct their energies to engaging more with their communities, rather than simply earning an income. It would shift our focus from economic growth, with doesn’t benefit everyone, to social and emotional growth, which would.

As a society, we would have to make an initial investment in UBI. But I believe that – quite quickly – we would be reaping the benefits of a more productive, fulfilled and cohesive society, and a society with far less mental – and physical ‒ illness. We need to do something radical to address our mental health crisis – why not UBI?

Matt Smith is Professor of Heath History at Strathclyde University