We tend to think about troubling questions about ‘being mad’, ‘being white’, and ‘being black’ separately rather than in association with each other.

I want to propose that much can be gained by exploring affinities between mad lives and black lives, and between histories that have frequently been ghettoised and emptied of their significance for mainstream historical narratives. Many authoritative texts have described black people and mad people as the products of disciplinary imaginations that only ever recognise them as problems. As the radical Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois famously asked in The Souls of Black Folk: ‘How does it feel to be a problem?’

To make any headway here, we must first acknowledge the historical sway of whiteness over human lives in Western societies and over the whole cultural apparatus of mental health. ‘Most white people’, remarks journalist Reni Eddo-Lodge, author of Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, ‘have never had to think about what it means, in power terms, to be white’. The politics of whiteness transcends the colour of anyone’s skin. ‘It is an occupying force in the mind…a political ideology that is concerned with maintaining power through domination and exclusion’. Of course, many white people are not self-consciously white and find the dogmas of ideological whiteness deeply repugnant. Even so, it is difficult to ignore the pervasive influence of a society in which being white has long been held up as the human norm. Whiteness is more a condition than a colour, proposes David S. Owen. It is ‘a deeply engrained way of being in the world’, and a structuring property of modern societies. ‘We are immersed in Whiteness as fish are immersed in water and we breathe it in with every breath’. Moreover, argues Robin DiAngelo, author of White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism, whiteness has always been predicated on blackness, and ‘anti-blackness is foundational to our very identities as white people’.

To understand how this can be so, we have to reach deep into colonial history. If slavery persists as an issue in the political life of black America, the African-American scholar Saidiya Hartman suggests, it is because ‘black lives are still imperilled and devalued by a racial calculus…entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery…I, too, am the afterlife of slavery’. Charles W. Mills, the Jamaican political philosopher, argues that liberalism has predominantly been a racial liberalism in which an egalitarian humanism has co-existed with hierarchical racism. China Mills, the critical mental health theorist, puts it more strongly in referencing the violence and radical exclusions on which liberal values have been built.

Amidst concerns over the rapid rise in the numbers of the ‘unfit’, among them the ‘insane’, from the late nineteenth century through to the Second World War, there were periodic alarms in the higher echelons of society over the quality of the population, or the national stock as it was termed. This provoked the fear of a sickness in the racial body that was threatening the future of the imperial race. ‘What are we going to do?’ asked biologist Julian Huxley in 1930. ‘Every defective man, woman and child is a burden’. Throughout this period, empire, and the future of the imperial race, provided the overriding context and reference point for standards of mental health and the expectations that were placed on individual lives.

In his Psycho Politics (1982), Peter Sedgwick chided radicals for the ‘extraordinary burden’ they placed on the psychiatric sufferer, expecting him or her to be a cadre in the counter-forces of socialist opposition. But this is only the obverse of the venom that was for long heaped on the mad person as a failed cadre in the struggles of the imperial race. Europeans were supposed to be paradigms of mental health, reflecting mastery and self-control. There was an enormous fear of loss of self-control and of displays of emotional weakness. ‘Nothing was so certain to bring a colony’s files onto the colonial secretary’s desk’, remarks imperial historian Ronald Hyman, ‘than the smallest suspicion that its governor was heading for a nervous breakdown’.

Europeans were supposed to be paradigms of mental health, reflecting mastery and self-control. There was an enormous fear of loss of self-control and of displays of emotional weakness. ‘Nothing was so certain to bring a colony’s files onto the colonial secretary’s desk’, remarks imperial historian Ronald Hyman, ‘than the smallest suspicion that its governor was heading for a nervous breakdown’.

Whatever else it may also be, the history of Britain and empire is a history of mental health in which ‘whiteness’ and ‘mental health’ are inextricably linked. ‘Mental health’ was identified with polite social behaviour and what the middle classes looked upon as civilised rationality. Mental ill health became a barometer of a moral failing to maintain the required standard of ‘whiteness’. ‘Being white’ was, above all, a moral condition that had to be worked at. It wasn’t a given and it could never be taken for granted. Remaining white and remaining sane were intimately linked as individual responsibilities that had to be renewed daily. Those who were unable to maintain these exacting standards were shunned and stigmatised as ‘poor whites’.

The ‘poor white’ problem, as it was known, became increasingly significant in Africa and India, especially, in the late nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries. A poor white was, at best, a dubious white, or sometimes not even considered to be white at all. Not quite right (or white). In the colonial imagination, European with nervous problems, especially those who were declared insane and segregated as lunatics were ‘poor whites’, morally, racially, and generally materially as well. Projected onto the figure of the mental patient was all that the imperial sensibility did not want to own.

At its most benevolent, imperial ideology viewed the ‘native’ and the ‘lunatic’ as childlike innocents, in need of humane care and of civilizing influence. However, under the influence of Social Darwinism, the lunatic was viewed as a regression to a more primitive stage of human development, or as a waste product of civilization. By the end of the nineteenth century, liberals had largely abandoned any residual belief in human equality. Among them was the explorer and writer Richard Burton, who treated the presumption by a growing number of ‘liberated’ Africans that they were his equals as ‘insolence’, warning that the ‘white man’s position’ would become precarious if the Black man were not ‘always kept in his proper place’.

Mental institutions and colonial environments alike were brought within the ambit of social evolutionary theories of mental development. Psychiatry is rooted in the colonial encounter with ‘alien’ non-European populations. For example, the categories and assumptions of classic psychiatry have their origins in the idea of the mad as inferior

Though the mental health survivor today is not the mental patient of yesteryear, psychiatry still emits the message that nothing has really changed. Patients are still treated like the same ‘inferior’, substandard natives who have long resided at the racialized heart of the psychiatric imaginary. Back in in 1989, Errol Francis and colleagues remarked in the Psychiatric Bulletin on the mistrust and suspicion felt by black people about psychiatry and related institutions. More than thirty years later, it would surely be fanciful to claim that the situation has improved markedly, if at all.

The writer and hip-hop artist Akala, aka Kingslee Daley, titles his recent trenchant polemic Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire. The ‘ruins of empire’ identifies exactly the terrain that mad lives, both black and white, inhabit today.

The distinctive thing about the contemporary mental health system is the continuing racialization of mental patient destinies whereby, for instance, black patients are subjected to Community Treatment Orders (CTOs) that require them to maintain strict medication and daily living routines or risk being returned to hospital, at nearly ten times the rate of white patients. ‘One of the greatest social fears for a white person’, remarks Robin Di Angelo, ‘is being told that something we have said or done is racially problematic’. Yet the psychiatric establishment has been less than eager to embrace or debate the suggestion that there might be something racially problematic about the CTO system. This seems to reflect a colonial legacy of division and denial that silences dissent and discourages or stifles any hint of alliances between disadvantaged groups. Developing alliances between mad lives and black lives, or between white mad lives and black mad lives, demands determination, effort and courage that runs against the establishment grain.

The Life and Defiance of Bill Moore

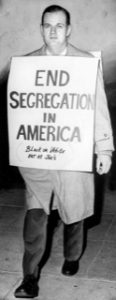

One former mental patient who was determined to maintain and advocate for such alliances, and paid for it with his life, was William (‘Bill’) Moore (1927—1963). Bill Moore was a white postal worker who in April 1963 set out on a one-man civil rights march from Chattanooga, Tennessee to Jackson, Mississippi to protest about the pervasive presence of white supremacy in American society. He did this pulling a two-wheeled postal trolley and wearing two sandwich-board placards, which read ‘End Segregation in America’ and ‘Black or White, Eat at Joe’s’.

While a graduate student at John Hopkins University, Bill had suffered a breakdown and between 1953 and 1995 was institutionalised at Binghampton State Mental Hospital with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. According to his Wikipedia biography, after his ‘release’ [sic] he became an activist for the ‘mentally ill’ and a civil rights activist for African Americans, undertaking three civil rights protests in the early 1960s in which he marched to the capital to deliver hand-written letters he had written denouncing racial segregation.

On April 23rd 1963 Bill was shot to death at close range alongside a highway in northern Alabama. Black studies scholar George Lipsitz was fifteen years old at the time and he can still remember the impact Moore’s murder had on him. A man who found white supremacy an abomination even though he was white himself, Bill Moore was ‘a rare individual’. ‘Few white people are willing to risk their lives in the fight against white supremacy’. In the courage and defiance with which he pursued human affinities and connections, exhorting us all to ‘eat at Joe’s’, the legacy of Bill Moore must surely resonate for us today.

Author: Peter Barham is a psychologist and social historian. A third edition of his book Closing the Asylum is being published, with a new forward and preface by the survivor activist Peter Campbell.

This is a sample article from the Winter 2020 issue of Asylum magazine

(Volume 27, Number 4)

To read more . . . subscribe to Asylum magazine.