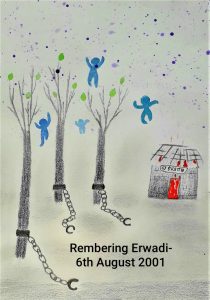

Twenty years ago, on the 6th of August 2001 a gruesome tragedy shook India, and indeed the world.

Twenty eight residents of a faith-based asylum for the ‘mentally disturbed’ died after being set alight in a horrific fire. The charred remains of their bodies were chained to their beds at Moideen Badusha Mental Home in Erwadi Village in Tamil Nadu, southern India. The few who managed to free themselves from their shackles escaped and five were hospitalised with severe burns. Investigation could not establish a cause for the fire.

Reporting the tragedy, the New York Times stated: “Care for the mentally ill is no source of pride in impoverished

India.” It was a scathing commentary on India’s approach to mental health care. Ravi Nair, the then executive director of the South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre was quoted saying, “the Treatment of the mentally

ill is a tragedy,” adding, “in both India and Pakistan, there’s this superstition that if a mental patient is kept near the

grave of a saint, they will be cured by some sort of hocus pocus.” Swiftly, a few days later, all asylums of this kind in

the country were shut and over 500 patients were placed under government care by order of the Supreme Court.

The owners of the asylum were sentenced to only seven years imprisonment by a magistrate’s court.

There has been no mass mourning for the victims, their plight almost forgotten, with barely any mention of a memorial. Erwadi wasn’t just about this one issue. It was about several issues that continue to plague the mental health system in India and the Global South. It would be wrong to talk about Erwadi while ignoring caste, class, gender and location, as these contributed to this tragedy. The combination of poverty and caste-based discrimination allows people little or no access to services. The narrative of ignorance, poverty and archaic mental health practices has its appeal. Third world poverty makes for a compelling spectacle: the more abject the story, the stronger the reaction. It also helps position some service users as more privileged than others. However, there is more to it than that.

While it wouldn’t be wrong to question the place of religious healing in mental health care, it would be misguided to blame religious healing for the malpractices that occurred that day. Religious healing practices haven’t always been helpful, in fact some have been downright abusive. However, in the absence of a nationalised healthcare system and affordable healthcare, dubious practices like this thrive. Another problem is that psychological services have mostly remained unregulated in India, with anyone able to call themselves a counsellor or therapist. Coupled with the shortage of licensed mental health professionals, and the economic cost of medical/psychiatric treatment, most people take what they can get. Tragically, Erwadi was one of those places.

However, the real tragedy is that Erwadi was not an aberration, it was a glimpse into a system that continues to subjugate vulnerable people. Horror stories of relatives being dumped in asylums, forced hysterectomies, physical and sexual abuse aren’t new or out of place. This is why shock seems a disingenuous reaction. It is not a secret that abuse occurs in psychiatric spaces, what is shocking that we don’t do enough about it. Lack of funding in mental health services and lack of professional training has led to a system that only functions for a few, if that.

In twenty years, little has changed, except cosmetically. Erwadi was the tip of the iceberg that revealed all the missing aspects of Indian society. The lack of infrastructure to deal with mental health issues, and paltry funds allocated to mental health from the health budget, mean that services are stretched to the limit. Suicides amongst women, students and farmers make headlines, however there is little action afterwards. For anyone outside the Indian urban middle classes, access to our paltry services remains elusive.

Every year awareness-raising events take place, warning of a crisis and recommending unhelpful individualistic solutions. But these are merely a performance. With no formal structures or access to services it is no surprise that people grasp at anything they can get. Voices of service users rarely feature in any discussion on policy change or in the organisation of awareness campaigns.

It would be easy to dismiss this as just a third world problem, but mental health services the world over are institutionally abusive and chronically underfunded. The things that make us vulnerable – gender, our sexuality,

race, caste, class and disability – are all exploited within this system.

So, as we commemorate the twentieth anniversary of this horrific disaster, we see some meagre improvements and developments in the Indian mental health system. Whilst legislation has changed favourably, those changes have

not adequately translated into significant improvements to the way we as a nation attend to our mental health.

If we are to truly honour the memory of those who tragically lost their lives in such a horrific, inhuman and undignified manner, the country must do so much more. It needs to start with a financial commitment to the cause, educating the population about mental health, listening to service users, encouraging people to train in professions that provide help and healing. This is especially important in these pandemic times which have seen a significant rise in mental distress. Without urgent action, this situation may only get worse.

Authors

Cynthia Stephen is a Dalit feminist activist and researcher; J. Sanjay Kumar is a psychotherapist; and Sonia Soans is a critical psychologist and member of the Asylum editorial group.

This is a sample article from Asylum 28.3 [Autumn 2021]. Subscribe to Asylum Magazine.