In this new series, two individuals – inspired by Asylum magazine but on ‘either side’ of the patient/professional divide – came together to exchange images (cartoons) and text (reflections) about what it feels like to experience mental health services.

The goal was collaboration. The process was joyful. The result was both art and alliance.

The Collaborators:

Images – Anne E Watmough (psychiatric survivor and cartoonist)

Text – Stephen McKenna Lawson (mental health nurse)

After an introductory discussion to agree the terms of the exchange, neither party had any say in the content of the other’s response. Each was completely free to respond in their own way. Anne was clear she didn’t want to add any text but to let her cartoons do the talking.

Whether or not you agree with the messages contained in this piece, we hope you will find it interesting. We hope you appreciate that we are not saying the experiences we depict are equivalent or universally generalizable. Our collaboration is a means to show – and try to understand – what has happened to us, and continues to happen to other people, in the mental health system.

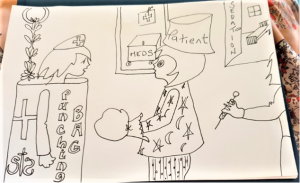

This first image was produced by Anne after reading Stephen’s article, The Paradoxes of Being a Newly Qualified RMN, published in Asylum 28.1. Spring Edition (available on our website)

Reflections 1: Negative for Some, or a Negative Sum?

The first image was produced by Anne after reading Stephen’s article. The Paradoxes of Being a Newly Qualified RMN, publised in Asylum 28.1 (spring edition) – available on our website.

My initial reaction to this image was not thoughtful. It did not contain thought.

It was physical: an expiration of air, a surprise outtake of breath. Different, but not unrelated, to an aspect of the experience depicted. It brought back my experience of being punched when I was a newly qualified staff nurse. This happened more than once. In a way, seeing this, I was winded once again.

Upon greater reflection, I find this drawing no less confronting.

I am labelled as a passive object – a bag. I’m an item with purely instrumental value: useful only when put to use by, or for, something else. As a punching bag, I am designed to receive intentional force that only ceases when the subject of that force is satisfied, or I’m broken.

Is this what my educators and managers had in mind for me as a newly qualified nurse? I can’t imagine that it was.

Writing this, I cannot help but also wonder: is this how some individuals feel when they are told, over and over, that they are schizophrenic or personality disordered? Is this how some people experience care and treatment? I can imagine that it is.

In labelling me as I never would have, Anne reveals her remarkable intuition. With a few strokes of black on white, she simply yet severely exposes a material truth of life in contemporary inpatient mental health services: that in spaces of supposed healing, there is violence.

In the period of my career on which my article was based, and to which this image responds, violence was common, manifold and multidirectional. It moved between the staff and patient group and also within the latter. Sometimes it was planned, other times spontaneous. Sometimes singular, other times all-encompassing. If this had been observed by an anthropologist, they may well have concluded that violence functioned like a cultural norm. Perhaps it formed the basis of the economy, a crypto-currency in circulation, the mechanism or means by which safety, rage and distress were expressed: the cost of doing business.

Sadly, even in places I worked afterwards, although they never felt as dangerous, violence of some kind still felt almost inevitable. And this included services for children.

But who/what is the source of this violence? If we consider the concentric circles of the patient’s eyes, and the partially disembodied holder of the syringe implying they also lack agency, the artist suggests the answer lies outside of individual behaviour. And I agree.

To my mind, what is presented here is an image of a healthcare system comprised of practices and structures that cannot help but damage (or at least threaten) aspects of everyone within it – whether those be their present, future, spirit, hope, confidence, trust or sense of self. To me, this image is a distillation of a negative-sum game.

This notion, that everybody loses, challenges the idea that power operates in services according to the laws of a zero-sum game where power is a finite commodity, one stripped or restricted from patients as it is hoarded by staff/services. It is a calculation in which one group wins at the expense of the other. Speaking candidly, as a staff nurse in an under-resourced, high-acuity PICU, I certainly didn’t feel powerful. I felt awful – despair even – at being engaged in something so far removed from what I thought caring would look like.

Life in a psychiatric unit needs to be radically different. It needs to look and feel more peaceful. The structures of health and care systems should cultivate relationships, joy and security, but it cannot do so consistently whilst orientated to disaggregated tasks, drenched in practices of risk and conflict managerialism.

In a sense, to become more caring – more care-full – perhaps we need to somehow become more care-free; free to care in ways aligned to the personalities, histories and needs of all members of healing communities.

This thought is offered sincerely, in solidarity, as a framing-device, a way of thinking which might help move us towards less coercive, more truthful, and deeply reconciled mental health services.

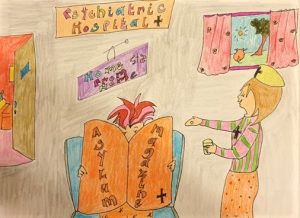

Reflections 2: ‘La Lucha hay que Buscarla’ (‘One needs to search for the struggle’)

This statement, made over forty years ago, is attributed to Luis Hernández-Cruz, a leader of the uprisings in, and later elected representative for, the Mexican state of Chiapas. As a title, it may initially seem very far removed from this image, and this exchange, but I think it is very relevant.

This image challenges us to find the struggles depicted within it. The absence of overt conflict, such as that depicted in the previous image, does not mean there is an absence of struggle. On the contrary, upon reflection, I believe we are transported to the heart of the political and cultural struggle for the future of mental health services.

The warm colours of summer and the idyllic, postcard-like image-within-an-image where the sun shines on plant and animal life, induces calm, quiet and stillness. Of all the visual elements, including the reference to Asylum, I am drawn most to the window-scene. I feel this operates almost like a key to the wider scene, projecting placidity from outside into the interior environment of the ward, which registers in the comfortable posture of the patient, reading in peace, and the friendly smile on the nurse’s face.

And yet…

It is not to the nurse’s expression that we are ultimately drawn, but rather to their activity – and thus their given identity – as pill pusher. Anne presents a view of ward life in which psychiatry-as-medicalisation is ever-present. From this point of view, the smile could now indicate a hopeful salesperson at work; a tool to help persuade.

The centrality of medication is the theme in Anne’s work that I find most challenging. As a mental health nurse who wants the profession to be recognised as a highly complex form of caregiving, to be reminded that this is not how it is experienced by many of the people we work with is at best disappointing, and at worst debilitating. But, in good conscience I cannot regard that viewpoint as unfounded.

Treatment options across healthcare are always subject to cost/benefit analyses, and psychotropics are no different. There is no doubt that medication is life-enabling for some people. I would be professionally remiss to suggest otherwise; guilty of perpetuating the stigmatising notion that mental health service-users cannot be helped in ways congruent with physical health patients. However, there can also be no doubt that medication can be life-limiting, in one way or another, to a greater or lesser extent, for others. I would be wilfully oblivious to suggest otherwise; guilty of ignoring survivors who speak of manifold harms and difficulties caused by biological psychiatry and instrumentalised nursing. I would also be closing myself off from the powerful testimony of movements such as Mad Pride, which champion madness as a self-liberating, not self-inhibiting, lifeforce.

Therefore, when examining the form of care on offer, I believe the question is not about medication per se, but rather what vision of care is manifest in current structures (economic and political) and practices (social and cultural). Here I believe there are only two possible answers: a minimalist vision or a maximalist one.

Anne’s image reveals the struggle to overcome the minimalist vision of care in which detention and medication are central to both professional roles and practices and patient.

But what could a maximalist vision look like? My answer lies in the specific memory evoked when I first saw this image.

One afternoon at the peak of summer, myself and four or five other staff members, alongside four or five individuals under our care, began dancing to well-known pop songs. In the glare and heat, what began as a planned activity led by professionals spontaneously evolved into a beautifully organic expression of community. The session was no longer controlled; it generated and then followed its own momentum. For a small amount of time, the only hierarchies that existed were who chose the music (not me) and who had clearly danced before (also not me). Honestly, it was an almost perfect moment; a Temporary Autonomous Zone that could have been anywhere in the world.

This memory is easy to recall because it was so exceptional and extraordinary. Nevertheless, it did happen, and I would argue that it is within moments like this that the blueprint for a maximalist, non-coercive, vision for mental health services can be found. We must design structures and practices that prioritise and promote fluidity, creativity and collectivity.

Caring is often described as being like a dance. In this instance, that was literally the case. The point, though, is not only the uniquely rupturing capacity of dancing. Other forms of communion might be equally powerful – it is the communion itself that matters.

Can we realise a future in which freedom and mental health services are no longer mutually exclusive? Or will freedom – even of a temporary, autonomous nature – continue to be something that happens elsewhere, outside of the windows and walls of our institutions.

….we welcome further responses about Anne’s cartoons (and Stephens’ reflections), from Asylum readers – in text or images. We hope this is the first of many collaborations like this.

This is a sample article from Asylum 28.3 [Autumn 2021]. Subscribe to Asylum Magazine.