I am a licensed physician in the United States of America, where the Supreme Court’s recent Dobbs v. Jackson ruling, overturning Roe v. Wade, nullifies constitutional protections on access to abortion.

If, instead of psychiatry, I had chosen obstetrics and gynecology as my specialty, I would now be threatened with criminal prosecution and incarceration if I continued to offer treatments that are clinically indicated and safe (in other words, if I honored my patients’ reproductive rights). I realized that it’s not that far down the fascist slope for psychiatrists to face criminal prosecution for honoring their patients’ civil rights in not committing them to locked units.

I did my psychiatry residency training at a large urban hospital that was right across the street from one of the city’s biggest homeless shelters. Many of the patients who ended up in the psychiatric ER were folks who had been kicked out of, or denied entry into, the shelter (usually because they were intoxicated). Psychiatric patients were triaged to an area officially called “Area D” but colloquially referred to as “the pen” – not as in penitentiary, but as in a coop where animals are squished up against each other (although either use of the word would have been appropriate). On Friday and Saturday nights, 20 to 30 men in various states of consciousness were crammed into a small area in the back of the ER. They were not allowed to leave until they had been assessed by a psychiatrist who worked solo on night shifts, which led to long wait times (and stressed-out psychiatric residents). It would have been impossible to plan for safe outpatient dispositions for so many people whose lives were in such disarray; by contrast, it took just a few minutes to complete the simple forms needed for involuntary commitment.

I am ashamed to say I involuntarily committed more homeless people at this time than I would care to remember.

Once I began to view psychiatric hospitalization as part of the carceral state, my threshold for taking this step has grown progressively higher. Over the last 15 years, I have evolved from a primary focus on medicolegal factors, which favor “being on the safe side,” to a more humanistic focus, which honors autonomy and reframes the idea of “being on the safe side” with the sad reality that inpatient units are, in fact, not safe for many patients. Once they are locked up, they are stripped of their belongings, allowed only very limited communication with supports, and subjected to other patients who may be experiencing psychotic agitation in extremis; agitated patients are not infrequently held down by multiple staff members and given intramuscular medications they do not want.

Trans and gender-diverse clients are vulnerable to trans/homophobic so-called “patient safety” policies which can further traumatize them. These include having to share rooms with patients of the opposite gender and being repeatedly referred to by their legal names rather than chosen ones. They are also often subject to harassment by other patients. I will no longer commit a patient to a carceral setting simply because I might get sued if I don’t, or it’s too much of a logistical hassle to come up with a less restrictive alternative. Now that I work primarily with queer folx, and hearing what happens to trans people in those kinds of places, I would not involuntarily commit someone unless I truly believed it was life or death.

In 2020, after a decade and a half as a public-sector psychiatrist treating exclusively folx with severe mental illness, I started my own private practice. As a prison/police abolitionist, I called it Uncaged Minds Detroit. I hired a young man named Jack as my office manager. He had a recent bachelor’s degree from an illustrious university, one to which he and I both owe many thousands of dollars. I, at least, had a very clear career trajectory to becoming a physician. Jack on the other hand, well he’s still not quite sure what he wants to become. But I saw in him a gentleness that I knew my clients would respond well to (I was right about this) and a person with lived experience (a lived experience that could not have been much rougher).

In his early 20s, Jack had experienced a textbook first break episode of manic psychosis. During his hospitalization he had been sexually assaulted by another patient. I’ve known Jack for over two years now but still have no idea what kind of scar this left him with. In any case, a couple years out, Jack is so scared of having another manic episode that he deprives himself of small, healthy pleasures because they might bring him dopamine: cardio, caffeine, marijuana.

In the last fall I began working with a client in his 20s. From his history I could tell he had legit bipolar I, but prior episodes were all linked to substance use. He had been an avid user of psychedelics and weed, but after giving up both of them, he psychiatrically stabilized even after self-tapering his lithium. He came to me unmedicated and expressed a strong preference to stay that way. I wasn’t about to tell him he should restart his lithium when he had absolutely no symptoms. So we agreed to monthly visits to check in and see how he was doing; each time, he seemed to be doing fine, and spontaneously reassured me he’d restart meds and contact me if he ever felt otherwise.

When he missed his last session with me, Jack checked in about my no-show policy, where I charge a small fee for missed sessions. I told him to waive the fee because engagement was key for this particular client and I didn’t want any barriers – I just wanted to reschedule the missed session ASAP, to make sure he was still doing okay off his medications. Later, in our team meeting, Jack told me there’d been a voicemail from the client’s girlfriend, indicating the reason he’d missed his last session with me was because he was in the hospital. She didn’t leave any more details.

“God dammit,” I said. Jack agreed, and added, “Yeah, when you told me the approach was stay off medications and see what happens, I was worried.” I took a stern tone and responded, “Yes, but I value patient autonomy.” I’d hoped Jack would pick up on my tone, but he doubled down with another comment about the risk of being off medications. I maintained my stern tone and said “I’m not going to shove meds down anyone’s throat.” We wrapped up the administrative part of our meeting shortly after, and I immediately told my two clinical staff I felt bad about speaking so harshly to Jack – especially because I knew his comments were stemming directly from his own fears of mania and hospitalization.

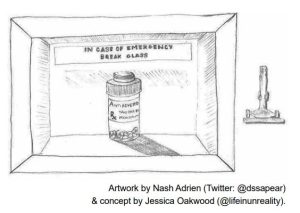

Unless I want to be a cog in the wheel of the mental health industrial complex, I have to value patient autonomy above all else. But it really makes me feel like a jackass when the result of my commitment to honoring autonomy is a different sort of commitment – a client’s admission to a locked psychiatric unit. Would a more conservative approach – more strongly recommending, or even insisting on, maintenance medications – have protected him from a potentially traumatic period of confinement? In that sense, am I not complicit in the loss of this client’s freedom? It feels a bit like a Catch-22.

The irony that Jack, the person with lived (traumatic) experience with mental health treatment, favors a more conservative approach than a psychiatrist was not lost on either of us; it speaks to the delicate complexities involved in making these decisions, which must be tailored to each individual client in such a way that turns my job from a profession to a craft – one that requires practice to master. Regardless, if the state attempts to influence my practice in the same way it has exerted its dominion over obstetricians, I hope I have the courage to fan revolutionary embers.

Lindsay-Rose Dykema, MD (she/her/hers) is a queer psychiatrist, prison/police abolitionist, and founder of Uncaged Minds Detroit, a mental health and wellness resource for low-income Detroiters, particularly the LGBTQ+ population and those impacted by the criminal injustice system. She lives in Detroit.

This is a sample article from the Autumn 2022 issue of Asylum (29.3). Subscribe to Asylum magazine.