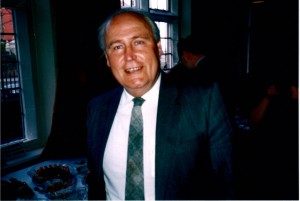

FA JENNER, MB, ChB, PhD, FRCP, FRCPsych, Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry (Sheffield), Profesor Visitante (Conception, Chile), was in practice for fifty years. After qualifying in medicine he was recruited to psychiatry for his expertise in research biochemistry. In 1967 he was appointed Professor at Sheffield University and found himself managing the psychiatric services for the whole of the Trent Region – a population of six million.

Meanwhile, he carried out the first double-blind UK trials on Librium and Valium, and became Honoury Director of the UK’s Medical Research Council Units for Chemical Pathology of Mental Disorders, and for Metabolic Studies in Psychiatry. Professor Jenner was also instrumental in a number of institutional reforms. In particular, he initiated the Phoenix House Drug Addiction Rehabilitation Unit at Sheffield (the second biggest in the country) and, responding to the appalling provisions for the elderly, set-up a psychogeriatric service (now known as specialist service of old age) for the city. He was the first Western psychiatrist to draw attention to the political use of psychiatry in the Soviet Union.

Despite initially believing in the so-called medical model of mental illness, in the light of the accumulated evidence Professor Jenner came to advocate social psychiatry. In 1986, his vision, organisational skills and financial help was vital in setting-up Asylum – the magazine for democratic psychiatry, and to keeping it going; he was also a regular contributor. In retirement, concerned with the topic which had always intrigued him the most, he at last found time to review the research and literature and come to his own conclusions, and published: Jenner, FA et al (1993) Schizophrenia: A disease or some ways of being human? Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Alec is an unsung hero. Aside from Laing and Cooper, in the UK he was perhaps the most influential psychiatrist of his generation. Since he was trained in chemistry, he understood better than almost any other psychiatrist of his time the actualities of the biochemistry and genetics of mental disorder – and demonstrated the absence of evidence for either kind of cause, or cure. He carried out and supervised key drug trials, but he also did much to promote the idea of social psychiatry, both in changing the focus of the services within his ‘domain’ to include the voice of the patient, and by inspiring a fair number of the next generation who passed through his University department and went on to make their own careers based on scepticism of the so-called medical model.

MEMORIES OF ALEC JENNER

Phil Virden, Executive Editor of Asylum magazine

I first met Alec in December 1984 – the year of Orwell’s dystopia, the year of the bitter miners’ strike.

That year it also became clear that the Government did indeed intend to close all the big old asylums and replace them with ‘Care in the Community’, augmented by a minimal number of specialised units. This policy was offered with a lot of talk about ‘liberalisation’ and ‘greater humanity’, although there was no coherent theory of exactly how this would benefit the many thousands of unfortunate souls who until then were supposed to be unable to fend for themselves in the outside world. On the political left it was suspected that the agenda was much more to do with turning patients out onto the streets to fend for themselves – or have others fend for them, out of compassion, and unpaid. This would cut costs and side-step the power of unionised NHS labour, and also provide a great opportunity for Thatcher’s friends to turn more profits, first of all from the sale and ‘development’ of hundreds of millions of pounds worth of prime suburban and out-of-town sites, and then from ‘farming’ the former inmates in private ‘homes’ with minimal standards of care, or simply as isolated tenants guaranteed to keep landlords’ properties full.

Actually, closing down asylums and setting up ‘patient-centred care in the community’ had already begun in Italy. This was at the instigation of a movement called Psichiatria Democratica. In response to conditions usually much worse than those found in the UK, that group had managed to organise various leftist parties and groups – and even the Catholic Church – to come together to get a law passed in 1978. Nobody in the UK – not least the Government – seemed to know how that policy was working out.

In 1984 Lin Bigwood was a psychiatric Nurse Tutor at Wakefield. She read an article about Psichiatria Democratica by Alec, and wrote to him. He immediately offered to lend her a Psichiatria Democratica photo exhibition, then showing at Sheffield. Although relentlessly obstructed by the top local NHS bureaucrat – a Labour machine-politician scared witless by the prospect of bloody revolution resulting from any mass meetings of workers (such were the times) – she managed to arrange a conference on the Government’s proposals. This featured the big photo display of the Italian experience, and the main speaker was a psychiatric worker from Trieste, one of Italy’s more progressive cities.

I seem to remember at least two hundred at the conference: all kinds of psychiatric workers, social workers, people from voluntary organisations (Mind, etc.), interested patients – and at least one or two NHS or local authority spies! There were speakers and workshops, and at the end a plenary session.

At some time during the conference I noticed a quietly confident, commanding looking man, about six feet tall, looking to be about sixty, balding on top, wearing specs, a leather jacket and an enquiring gaze. He was hard to miss, and obviously a man of some authority, since he swept through the big room trailing an entourage of perhaps a dozen younger men and women. At the plenary session it turned out that this was Prof Alec Jenner, and that in his group were junior doctors, psychiatric workers, students and interested patients who were all very interested in the Italian experiment.

This conference was notable for the enthusiasm of the participants. There was much at stake, but it seemed that the Tory policy might yet turn out to be a great opportunity to introduce a far freer and humane kind of patient-centred psychiatry.

Towards the end of the plenary session I got up and said as much. I suggested that it might be a good idea for all those committed to a more liberalised kind of psychiatry to keep in touch so that they could reflect, agitate and campaign together. And if there was a ‘whip-round’ and people would put their names on a list, I would organise, print off and distribute a record of the papers delivered that day, in the form of a booklet. I seem to remember about 130 people signing up for that.

As the conference began to break up, Alec approached Lin and me. He said he liked my idea and had already been thinking of starting a magazine, as an accessible alternative to the stuffy and elitist professional journals, so as to offer some kind of ‘open forum’ for anyone interested in debating mental health matters – whether doctors, patients, family members, other health workers, whoever… This seemed a great idea, so we agreed to meet again for that purpose.

Alec offered his home outside Sheffield as the venue for meetings, once a month, on a Sunday evening. I recall this happened throughout 1985. The first time we turned up, the Jenner’s fair-sized lounge was packed tight with the people Alec had gathered. They ranged from patients to doctors to grad students to social and psychiatric workers. Whiskey, wine and fine cigars were in good supply, as well as hot drinks for throats dry with all the talking and smoking. (Yes, smoking was common in those days, even indoors!). Instead of down-to-business, these meetings mainly turned out to be great social gatherings and exchanges of ideas. Alec seemed to be in his element, and his wife Barbara was endlessly patient and solicitous.

Meetings were quite free-form. Although a few people did stay the course, most of the participants seemed to change quite often, so that we regulars were forever having to ‘fill people in’ as to what we were about and what we had already agreed. And then there was the inevitable clash of egos and the covert and not covert so politicking… But in the face of the solidarity of the faithful few, those people gave up and didn’t return.

‘The collective’ became (and still is) roughly whoever was there or contributed. I would guess we were all firmly committed to contesting ‘the medical model’ but we welcomed any reasoned view on any mental health issue. A policy was certainly formulated – no party line, complete freedom of debate – but none of the core members were ever interested in formulating a constitution. We trusted each other.

In the end, after much vacillation, we decided to produce the magazine quarterly, and to call it Asylum. The name was suggested by Tim Kendall (who now writes the mental health Guidelines for NICE) and heartily endorsed by Barbara: it was an ironic nod to the original 19th century house magazine of the psychiatric profession. The first issue, for the summer of 1986, featured articles by a variety of interested parties – doctors, patients, ex-patients, psychiatric workers. In the middle was Lin’s exclusive interview with RD Laing – probably his last.

Over the years the magazine had its share of ups and downs, fits and starts. From the beginning, and for fifteen years or so, Alec acted as business manager and public face of the magazine. He willingly rode to the rescue more than once, when the magazine got into a pickle with its printers or its finances.

My experience of Alec, over two decades or so, was mostly as a co-worker on regular Asylum business, usually several times a year. And then, during the last decade or so, when he had to give up playing any part in the organisation of the magazine, I only saw him sporadically. Although we lived far apart, he remained a firm friend, and he and Barbara remained the most hospitable of hosts when I occasionally visited their hill-top lair.

I always found Alec warm-hearted and generous, open and unflappable. He combined a deep commitment to the theoretical and practical issues of psychiatry with an entirely unpretentious, affable and approachable manner. I can imagine he would have been as solicitous and reassuring, but serious and pragmatic, with his patients as with anyone else. In fact, I witnessed it: as a matter of course, patients and ex-patients were always included in the collective and in the work around the magazine.

After retiring, I guess when he stopped rushing around so much, Alec’s aspect began to morph into one uncannily like Bestall’s image of the jolly professor in the Rupert Bear stories – a kind of avuncular, huggable bear of a man.

Alec said he owed much of his demeanour, drive and moral sense to his father, a self-made man who by hard graft and canniness had worked himself up from his trade into a successful house-builder. He told me that as a boy he had been much impressed when his father simply gave away one of his new-builds to a loyal worker who couldn’t find the cash to house his family.

So as to give him advantages his father had not had, Alec was sent to a minor public school. Although this clearly gave him the advantages of a good education and separation from the regional accent of his childhood (still very important in those days), Alec had none of the posh talk or snooty condescension so often adopted by those with social advantages. On the contrary, Alec was sometimes almost embarrassingly conscious of his good fortune, his power and privileges, and of his duty to ‘give something back’.

It must have been this feeling that led him into a life devoted to a form of practical compassion, and one in which he could use his lofty position in psychiatry and academe to quietly carry out acts of generosity. For example, many friends and acquaintances seem unaware that when he retired he was still in demand for the easy and extremely highly paid work of consultancy and Mental Health Tribunals. Alec decided he could either do the work and pay himself but also pay the taxman a fat whack, or put all the money into a trust for the benefit of projects he would like to support – i.e., hard up people who were never going to get any official funding. So for at least ten years, this is what he did – to the tune of tens of thousands of pounds.

Alec was, as they say, a one-off. For most of her working life, Lin Bigwood has been around all kinds of mental health work – from closed wards to geriatrics to forensics to A&E and ‘in the community’. Although they never did any psychiatric work together, she spent a fair amount of time around him, and she reckoned that Alec was one of the best psychiatrist she ever met.

Alec Jenner: my reflections

Helen Spandler

I was deeply saddened to learn of the death of Alec Jenner, co-founder of Asylum: the magazine for democratic psychiatry. I met Alec in 1992 when I went to Sheffield to study a course he helped set up with Tim Kendall (an MA in Psychiatry, Philosophy and Society). Alec had seen an undergraduate essay I wrote about the German Socialist Patients Collective (SPK) which was later published in Asylum (in those days the magazine published anything!). He wrote to me encouraging me to come to Sheffield and helped get the university to waive my course fees. When I arrived Alec had just retired but was still a key presence in the Department doing the occasional lecture and regularly attending the monthly Tuesday evening discussion forums that he’d established. He was also still heavily involved in Asylum magazine and had regular collective meetings at his farmhouse (in those days, members of the collective usually went home clutching half a dozen eggs or a jar of honey). It felt quite laissez faire, but ultimately a pretty democratic arrangement. Alec and other members of the collective would regularly invite people along to meetings, including current and former patients, who often visited him and even stayed at his house. Whoever turned up for meetings would be part of decision-making and effectively part of the collective. Many people came and went, but for many years Alec held the magazine together, using his home as its base.

Alec knew how complex madness and psychiatry were & what enormous ethical issues they raise for society. He wasn’t going to simplify it for the sake of his career or to make a big name for himself. He had no axe to grind and no line to push. He was never one for grandstanding, for making claims in the name of ‘radicalism’ – a tendency that often besets the mental health field. He was not guilty of what Peter Sedgwick called ‘psychopolitics’ (the tendency to use madness to justify a particular radical ideology at the expense of the needs of people affected). In this sense he espoused a real politik – a politics defined by pragmatism not ideology. Neither was he prepared to abdicate responsibility for trying to relieve the suffering of others (even if his efforts were, by his own admission, sometimes naive, clumsy or ill-advised). He knew he was socially privileged – by virtue of his class, status and education – and he wanted to use this position for the benefit of others. This might sound crass, but how many people can truly claim this?

Neither was he afraid to raise awkward questions. For example, when he wrote an unpopular article in the pages of Asylum defending ECT (in very exceptional circumstances). No decent human being likes the idea of electric shocks through the brain. It offends our sensibilities. However, I know people who swear their lives were saved by ECT when nothing else worked. What do we do about such claims? Do we say they are deluded or suffering from false consciousness? Alec didn’t seek controversy and he wasn’t in favour of ECT, but he did want to have a genuine debate about the issue – a debate which is still long overdue.

Perhaps Alec’s political libertarianism didn’t always lead to wise choices, for example when considering an article defending paedophilia or deciding to publish an article by the False Memory Society. (But if you didn’t turn up to a collective meeting, you didn’t get a say!). This revealed how naive and traditional Alec could be at times. He freely admitted that he found some of the more recent critiques of gender and sexuality hard to stomach or even understand. I vividly remember him giving me a poor grade for a paper I wrote about trans-sexuality. Although I don’t think he really ‘got’ the gender politics of it all, a lot of his feedback was spot on (much of my essay made little sense!)

Most of all, Alec was open minded and always prepared to try and understand different views and perspectives. He tried to reflect and understand the world as he encountered it – in all its contradictions – through his research and practice. In that sense he was an empiricist, a scientist, in the best sense of the world. (Unfortunately, both are often dirty words nowadays.) He didn’t just surround himself with people he agreed with, who would buttress his own view of the world. He purposefully tried to create a space for alternative and marginalised views, whether he agreed with them or not.

Both myself and Terence McLaughlin (editor of Asylum magazine 2000-2007) tried to convince Alec to write an autobiography or let us write his biography. In typical modesty he declined. Yet he remained ever generous in recounting his experiences to the many people over the years who sought his advice, and lending out his books from his vast library – many of which I’m sure he never got back! A biography would have made for fascinating reading, as he was closely involved in some of the best and the worst aspects of modern psychiatry, as well as resistance to it. He sat on both sides and was never overly defensive or unnecessarily attacking of either. Indeed, he rarely saw them as opposing sides. Whilst people could be hyper-critical of Alec (he was either not radical enough, or too radical for some) he seemed to take criticism in good heart, and his door remained open. If we need psychiatrists (and that’s another debate that still needs to be had) then I believe Alec was the kind of consultant you’d want to see – he genuinely saw his role as being someone people could ‘consult’, rather than a medical expect.

Alec started out as a bio-chemical research psychiatrist (he instigated in the first trials of drugs like Valium); yet he was also open to anti-psychiatry (and especially social psychiatry) and he was very supportive of the emerging patients/service users movement – he was involved in the service user run project McMurphy’s in Sheffield in the 1980’s & 1990’s. Ultimately he was a powerful advocate for a more humane and democratic psychiatry. He was never afraid to hold his hands up and admit his mistakes – another rare gift. I think it was Alec’s own doubts about his practice and the mistakes the medical profession made with the (over)prescribing of benzodiazepines that made Alec ready to question current orthodoxy and listen to dissenting views. He knew only too well that psychiatry’s next big mistake might be right around the corner.

I admired and respected Alec enormously. I experienced him as warm, kind and generous with his time. He had a calm humility that continues to inspire me and drive my vision for Asylum magazine – to truly offer a space where contentious ideas can be aired and discussed openly and honestly, without pre-judgment or dogma. I hope we can continue to honour Alec’s contribution by keeping alive the spirit of Asylum magazine..

Remembering Alec

Phil Hutchinson

Last year I was allotted a doctor from Italy. I mentioned psichiatria democratica, Franco Basaglia and Trieste.

Dr. Emilio di Campo, looking suitably alarmed, asked me how I knew about these things. So I told him about Alec Jenner.

I first met Prof Jenner in a Social Services hostel in Sheffield where I’d been persuaded to see a psychiatrist. I was afraid, because of my mother’s history of mental illness, hospitalisations and the treatments – ECT and heavy medications – which had hideous physical effects and, I believe, long- term toxicity which contributed to the strokes which shortened her life.

I was going nowhere and had recently started to hear voices. Jenner, accompanied by a student, had a piercing gaze which, if I’d attempted to bluff, would have seen right through the pretence. I was actually defenceless. That gimlet eye – and now I say that, I am conscious of what he would have suffered as he progressively lost his eyesight – was accompanied by a compassion for the human condition, our frailty.

I came to comprehend that this man was to be respected as a master of his craft, able to draw people out of themselves and, with his oversight of Sheffield University’s department of Psychiatry and Ward 56 at the Northern General Hospital, draw people together. His interest in psichiatria democratica informed his encouragement of dialogue, conversation between all actors in the culture of mental health, of treatment and recovery; between workers in their different roles and recipients of services.

In the 1980s there was particular interest in establishing Patient Councils, following what was happening in Holland. Regrettably, the UK has not as yet made it a legal requirement for employers and providers of services to have places on their boards of directors to shape, in an organic way what is produced, whether it be a care service or a manufactured object. What we have are market- orientated consumer watchdogs and customer satisfaction tick box questionnaires. Indeed, we feel like the manufactured objects.

The founding of Asylum magazine in the mid-1980s was also part of a nascent democratic movement within mental health services.

It was after I’d left hospital that someone showed me The Guardian interview with Alec which prompted a dramatic boost in sales. At an out-patient appointment he suggested that I might write something about the different kinds of treatment I’d taken up – what had helped and how had it helped?

A few months later I was part of Seven Hills Trust which was a voluntary employment project for people who’d been through mental illness, mentally ‘less abled (to fit into a ‘normal’ working environment) and also people on probation. Alec was one of its directors and trustees. (This trust was refused funding by the Sheffield NHS mental health administration.)

Asylum’s momentum had stalled due to problems with the community project in Huddersfield where it was printed and distributed – or not. People were demanding refunds and legal action.

One Sunday afternoon I was picked up by two psychiatrists and a social worker (Tim Kendall, Steve Ticktin and Rick Hennely) at my council flat in which I’d succumbed (it was nerves) to drinking home brewed alcohol whilst waiting for them. We were en route via Manor Farm, Brightholmlee to pick up another of this gang of disreputables, before going on to ‘Minnow’ at Milnsbridge, so as to salvage Asylum.

It was quite a messy operation. A few days later, the magazine almost totally foundered, when several hundred back issues flew out of Tim’s hatchback car, along the Holme Valley. I was then installed on O floor of the Hallamshire Hospital, in order to sort out some kind of methodical system, pre -internet, for making sure copies were sent out. The copy for the magazine was posted by Phil Virden to be collected at Sheffield Station, and then printed at Monteney Community Workshops on Parson Cross.

For me, all this was better than any after-care plan, all written out. If it effectively happened that way, then it was a case of it being made up as we went along, and it took my willing participation in whatever Alec’s, Tim’s and the Asylum collective’s ideas were.

I can honestly say that this period of my life was transformatory. At first I had fears, but knew I had to take risks or become ‘just another mental patient’. My confidence grew. The Prof would say that now I thought I was running the whole show. (He also would say at times that his secretaries were better psychiatrists than he was.) Alec’s students had living material next door.…

I can see that, as an educationalist, as well as a practitioner in psychiatry, Alec never stopped being open to learning and trying different things . He would talk of trust being built gradually. There were so many wise observations with which I agreed, even though I felt inadequate in putting the wisdom into practice. But, then, Alec would always be honest about what he felt his own shortcomings were.

People would criticise him seeming to advocate ECT, and some of his other views. He enjoyed that. They overlooked the fact that, as the Head of a University department, he had a role to foster debate – that this was part of shaping what would be taught, and what treatments might be tried and adopted. He could not change ‘the system’ except by contributing to a change in its culture, its guiding principles – which he did, significantly.

Those who might slander him seemed to lack the humanity which he afforded them.

Later I read about Alec’s part in the formulation and widespread prescribing of Valium. He must have been very worried about his career and his family, who were very important to him. (That was another value which he would stress to me as worth having – that of good, healthily functioning relationships as a cornerstone, a foundation for whatever we do as individuals. Again, I felt he was right; again, I struggled…)

Perhaps it was this critical episode which led him towards a view that self-understanding and management of one’s condition is the best we can hope for; and from there to push one’s abilities as far as one can in taking a positive part in society.

Those who set up doctors and other professionals as gods often turn against their idols. I once mentioned God. “Well he won’t help you,” Alec rapped back. He would sometimes ask if there was “anything we can help you with”. This life we’re all compelled to would surge up into my mind. There was only one answer, always: “No”. He may have appreciated that. On the other hand, he may just have had to get back on the phone to Barbara after she’d filled up the petrol tank with creosote.

Undoubtedly, Alec inspired affection from me and many others, but I always felt there was a necessary line and boundary of respect and roles between us. After he retired, and I had also gone about making the mistakes of life on my own, he would write and there would always be something that I’d remember. Occasionally it was memorable for obscure reasons. “Life is like golf – not that I’ve ever played it!”

I was fortunate: when I was in a crisis the luck of the draw referred me to Prof Alec Jenner.

Thank you.

Reflections on the Death of Professor Alexander Jenner

Dr. Stephen Ticktin

I was very saddened to hear recently of the passing away of Alec Jenner. He was a rare gem in the psychiatric field, a true scholar, and a gentleman. I first heard about him in the early 1980’s from my teacher R. D. Laing who mentioned him as a professor of psychiatry in Sheffield who was sympathetic to his writings but I didn’t get to know him until the late 80’s when he launched a new magazine together with Phil Virden and Lynne Bigwood called Asylum: A Magazine for Democratic Psychiatry. I believe it was Phil and Lynne who originally came up with the idea of the rag and they broached it to Alec who was all in favour. He roped in his bright blue-eyed lecturer in the Department of Psychiatry at Sheffield University, Tim Kendall, and the magazine was launched. Rick Hennelly and Paul Baker were also involved in those early days. Asylum was in some sense a salute to the progressive work done in Italy by the Italian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia and his group Psychiatria Democratica. Basaglia’s motto was simply this: rather than creating therapeutic communities why not make the community therapeutic. This led to the deinstitutionalisation of a number of big psychiatric hospitals in Northern Italy.

I remember well my first meeting with Alec. I think it was in the winter of 1987. I was working as a clinical assistant at the Drug Dependence Unit at University College in London just off Tottenham Court Road. Alec arrived lugging a big box of the first issue of Asylum magazine. He was all bundled up and sweating profusely—he was a heavyset man who weighed about 250lbs. We had a great chat in the foyer of the Unit and he thanked me for being willing to help distribute Asylum in the London area. He wanted me to make contact with Donnard White who was already involved in that regard. I did so and Donnard and I became the main distributors of Asylum in the Greater London area. I believe Donnard had been a student of Phil’s at York University. He was politically savvy and we had a great friendship for about 7 years.

Asylum meetings were usually held in Sheffield. The initial editorial collective was a somewhat motley crew made up of people from different parts of the U.K. Some of the early productions of the magazine were a little sketchy. Alec was the presiding presence but at the same time he always promoted a democratic spirit within the group. Anyone involved in the mental heath system such as doctors, nurses, social workers, and patients, were all encouraged to write in their views or contribute to the magazine in whatever way they could. General issues were the norm but we also started doing special editions as well. I can recall being quite involved in the one we did about Ronnie Laing subsequent to his death in 1989 (Volume 4.2)

The magazine seemed to dovetail nicely with the development in the 80’s of a number of grassroots organizations such as CAPO (Campaign against Psychiatric Oppression), Survivors Speak Out, The British Network of Alternatives to Psychiatry, and The London Alliance For Mental Health Action. I always enjoyed going up to the meetings and seeing Alec. I think I had a bit of a crush on him which I’m not sure he was aware of. One of my fondest memories was getting lost with him en route to an Asylum meeting. He suffered with glaucoma and had difficulty with his vision. He was also something of an absent-minded professor so while he was in the midst of regaling me with anecdotes from the history of psychiatry he suddenly became aware of the fact that he had lost his way! We arrived at the meeting half an hour late! But the whole experience for me was an exquisite pleasure!

I often thought of Alec as being, in some sense, akin to Eugen Bleuler, the Swiss psychiatrist who had coined the term schizophrenia at the turn of the 20th century. Bleuler was, for his time, a progressive thinker and supported the work of more radical pioneers like Freud and Jung. For me the psychiatric pioneers of the 60’s were Laing and Cooper and I felt that Alec was likewise supportive of their very critical work. He himself never quite abandoned the medical model and one of his earlier projects was researching the causes of affective disorders for The Medical Research Council. However his resonance with Cooper in particular was striking as, temperamentally, they were both very similar—very thoughtful compassionate men with strong social consciences. Cooper once referred to himself as a Marxist-Luxembourgist and I believe Alec, in one of his contributions to Asylum, called himself a Marxist-Gramsci-ist.

The last time I saw Alec was at a conference in Sheffield in 2002 where Pat Bracken and Phil Thomas were speaking. We had quite a nice chat with Terry McLaughlin during the intermission in the quadrangle outside. When the conference was over I said goodbye to him with a slightly awkward hug. It would be the last time I would see him. In 2004 I returned to Canada and we virtually lost contact with one another. Interestingly enough I had been thinking recently of writing to him. I’m currently in the process of putting together a book consisting of various articles and book reviews I have written over the past 30 years some of which had been previously published in Asylum. I call it “Queer, Jewish, Hippie, Shrink”: The Collected Papers of Dr Stephen “The Dude” Ticktin: Philosopher, Psychiatrist, Writer, Musician : In One Slim Volume. Alec would have been the ideal person to write the preface.

October 2014

The Dude Abides

ALEC JENNER – IN HIS OWN WORDS

Around the turn of the millennium, a decade or so after retiring from full-time work, Alec was interviewed about his career.

He started by saying he had always been interested in psychiatric matters.

“Even as a schoolboy I’d read quite a bit of Freud, because the English teacher I had was very interested in psychoanalysis…. So I started with that sort of interest and was the sort of kid that read more than some, and converted easily to idioms such as psychoanalysis, Freud and Marx, Wittgenstein and AJ Ayer, and Julian Huxley and HG Wells, Bernard Shaw and so on. I’d also had quite a religious background, but I’d become by then a sort of scientist. So I was immensely interested in psychoanalysis, but equally or more so in physics, chemistry and mathematics. I actually went into the Navy instead of doing maths, but a chap told me I’d make more money being a medic, so I decided to do that when I left.”

So he went to Sheffield for the medical course, and a PhD in a chemical subject, and at that time “thought that I knew the explanation of manic-depressive illness”. He went into psychiatry via medical and bio-chemical research. Influenced by certain well-established, biologically-inclined psychiatrists,

“I had a generally sort of ongoing interest in psychiatry but held the intensely ‘scientific’ view that in the end the mind could be explained away chemically… At that time I thought a newly discovered hormone, aldosterone, would explain manic-depressive illness…”

While still a graduate student, Alec so impressed the Professor of Psychiatry that, despite no training in psychiatry, he was offered a job as lecturer at Sheffield University. Research took him to Norway, the beginning of his international contacts. In the event, that research did not come up with any amazing discoveries, but it did usefully serve to disprove certain theories of hormone or chemical causation of mental illness.

After this, Alec was supported by the Medical Research Council and started his own project concerning manic-depression and hormone rhythms. The research didn’t seem to be working out, but then

“…the penny began to drop… Piece by piece, chinks of light appeared through the biochemical approach. It struck me then, with this particular patient, that you could either change the cycle [of behaviour] by giving him a simple chemical, Lithium, or by moving him, by changing his social context. Really, I think then a long-term interest in philosophy raised in my mind the problem of defining what is fundamental. In other words, the condition is context-related as well as chemically based.”

Sheffield was a city afflicted by smog from the steel industry, and Alec was well aware that in one sense ‘the cause’ of the rickets still rife in the poorer areas was a lack of Vitamin D, but in a more fundamental sense ‘the cause’ was the terrible local pollution.

“It struck me that using Vitamin D for rickets had held up smoke abatement and the improvement of children’s natural health for a very long time. So that raised for me the issue of what one means by ‘fundamental’. After all, Vitamin D as a treatment of rickets did not constitute an attack upon the fundamental causes but merely ameliorated the condition.”

It seemed to him that ‘the causes’ of mental disorder, and the response (treatments) to it, might be viewed in a similar light.

“The other thing that occurred to me came from my interest in music. The note of a violin string depends upon its thickness but also upon its tension. I began to think that the onset of psychosis bore a relation to the tension of the situations the person lived through, and that this might have an effect on the rhythm [of manias and depressions]. And then it struck me that the patients lived in pretty grim and isolated circumstances in the old style mental hospitals, existing on a constant diet and with not much to look forward to, really, until a film crew turned up [to document the study] and the cycles broke down.”

This was in the 1950s, when promising psychoactive drugs were just being introduced. Alec’s attitude was that

“If the Vitamin D equivalent works – in the case of the ‘disease’ of psychosis, chlorpromazine – it must be economically interesting. If there is a drug to stop a child’s knees bending with rickets, it’s going to be used. So now perhaps a similar effect can be made on people called schizophrenic. You could say, with Ronnie Laing – who by this time I had met – that it’s all to do with the family structure. But you aren’t going to change that side of things very easily. But if you give the son or daughter chlorpromazine everybody finds to their delight that a lot of the mad ideas disappear!”

* * *

There was not one eureka moment, and Alec admits he was never entirely clear in his own mind, but he definitely moved away from a blind faith in internal, biochemical or genetic causation, towards social psychiatry. The big old psychiatric hospitals were falling from favour, and the idea of community mental health services was on the rise.

In the 1960s Alec was getting plenty of funding from the Medical Research Council, was made Director of the Medical Research Council Unit, and became Professor of Psychiatry at Sheffield University. Luckily for him (if not for all the people for whom he was providing with employment), the research ran down, because when he was made Professor there was only one for the whole of the Trent region, and he became responsible for managing the services for a population bigger than that of Scotland. He was “on every appointments committee from Leicester to Lincoln to Nottingham, Derby, Barnsley – everywhere.” At the same time, he was carrying out the world’s first studies on the benzodiazapines, Librium and Valium. In his spare time Alec was involved in leftist politics, and in the 1970s he also got involved with protesting Russian dissidents being locked up and treated as mentally ill.

Alec was interested in RD Laing’s ideas about family dynamics generating mental illness, and spent a bit of time with the famous counter-cultural guru. However, he didn’t find that time particularly useful. But he did pursue his interest in the contextual effect upon patients’ behaviour, including introducing practical changes in the ways patients were to be treated in their everyday routines. He began to listen much more to what patients said, and to make sure, if he could, that nurses responded helpfully to their reasonable wishes. By now he had realised that so many of the patients clearly had exceptional difficulties in their home lives or upbringing.

“And so it struck me that another mistake I had originally made in psychiatry was to discuss psychopathology with the patients rather than to discuss life with them. I was always interested in what sort of hallucination they had, and whether it fitted in with Schneider’s classification, and things of that sort. But I didn’t bother with that with this particular [patient]. We talked about what he wanted to talk about. I also thought that the patient had as much right to an ego as a Professor of Psychiatry. Because the professional situation was such that my ego was being pumped up. Wherever I went everybody thought I was The Great Expert and the patients were the riff-raff…

This patient did quite well. And it struck me that part of the success was due to there being a future for him, and because he began to see that the way he was playing his cards in the real society was mistaken.

What also impressed me was that many patients could be surprisingly normal in many situations. It became clear to me that the way you handled the patient was very important. I suppose that this idea of a special role in life is central to the problems of a lot of people. All human beings need to feel special in some way…”

Prompted by a junior colleague, Alec began to take more risks, allowing much more freedom – even to some “frightened” and “outrageous” patients. It now seemed obvious to him that responding violently or with more oppression increases the violence that is already the problem. He found that

“…giving the patient his freedom and respecting his wishes, instead of trying to stifle him by locking him up, actually did lead to a way out of the [very fraught] situation.

It’s difficult for people today to understand that our generation was brought up in a tradition that separated physical illnesses from any sort of psychological problems, which were seen as a visitation upon the brain. It was thought that you must rush in and give the treatment to the schizophrenic quickly otherwise the chances were he would quickly get a lot worse. The treatment, of course, was when they discovered the phenothiazenes. Talking to people took a back seat, really.”

By this time Alec had already lost faith in the possibility of any outright biochemical cure. Despite a huge and continuing research effort, no bio-chemical, hormonal or genetic cause for any functional mental disorder was ever discovered (in his time or since). It should be noted that Alec was one of the very few psychiatrists – probably in the world, but certainly in the UK – to be properly trained in bio-chemistry, and to have a genuine working knowledge of it. So his movement towards a social psychiatric perspective was driven by the evidence – not, as with so many psychiatrists, by what he wished was true. However, he never believed that biochemical or genetic research should stop.

“But I also think that there is a whole area in which medical or technical discourses are convenient gobbledegook. I suspect that people have a great need to all speak the same gobbledegook together. I think psychiatrists should be increasingly aware of the treachery of the words they use.”

Two particular “very violent” patients confirmed the loss of his previous blind faith in the bio-chemical basis to mental disorder: their behaviour suddenly “transformed” when they were listened to, given respect and allowed more freedom

“So then I became rather frightened: without the medical certainties, what the hell would I do now?”

* * *

Being a senior academic as well as a practicing psychiatrist, Alec was not able to give very much official time to many individual patients. However, he made sure he kept in touch by regularly seeing geriatric and ‘drugs’ out-patients. In effect, a very busy manager much of the time, dealing with the internal machinations of his Department, with the Hospital and units, with research projects, with local and central Government (the NHS) and their various agencies, he found it best to press gently for whatever he wanted, rather than be confrontational.

He recollected that he was probably not a brilliant lecturer – probably because he wasn’t entirely sure what he believed, anyway. It seemed to him that “the medicalisation of people’s problems is a very confusing area.” He also

“…always thought it wise – and I was never forgiven much for it – to admit that psychiatry has a policing function. Society requires some sort of thought police, in some sense. That’s putting it rather crudely. But I think that much of mental illness is that which is not approved of, but for which the society’s concepts of justice just don’t work. This is largely because the whole notion of agency, the whole idea that there is a self that actually chooses, is problematic. I think we have an everyday way of working which might make very good sense, but if you enquire too closely into problems of freedom and choice, things become less clear. I can’t see that a society can operate without the assumption that people are responsible for their actions, or largely so, unless you make a special category that people can enter into – something like an illness which means they are not any longer responsible. Of course, this is where psychiatry comes into it, dealing with that special case.

If this is so, psychiatry does then have a function of controlling that which must be dealt with irrespective of justice… The concept of Thought Police is a bit chilling. But I never took the totally radical view that it’s wicked to be a policeman. I think society needs sophisticated and responsible policemen, and I spent a lot of time trying to work out how to be a self-respecting policeman, amongst the other jobs in psychiatry. There it is. What do you do with the big problems that do arise?

After the radicalism of the 1960s and 1970s there’s been a tendency towards conformity. But I think Laing and others went too far. I think what they failed to see is that it isn’t wicked to have a police force. They had some idea that if you ‘let it all hang out’ it would all be all right. But I don’t think things are as simple as that. It was utopian. They were against planning anything for the future, and just wanted to smash the bad reality they saw around them, and would think later about what should replace it. I think there was something infantile and adolescent about that sort of attitude.

I would rather be an adult who recognises that you can’t be nowhere in history and society, the same as you can’t be nowhere geographically. You are here. And here has everything from a given language to a given politics. To some extent I thought the confusion of the schizophrenic was that he thought he could have an accurate language of his own. And that is not possible, without depending on the language he was given. Even if he uses metaphors, they are based on the language. It’s like wanting to kick a football with two feet – very original, but disastrous! And I think the cultural revolution of the 1960s, in a wave of excitement, tried to kick a football with two feet. Of course I was made a professor in the ‘60s, which was a mixture of excitement and fear, really. Because the students were always occupying something or other and psychiatry wasn’t that popular!”

In the 1970s, already a Fellow of the Royal Society of Psychiatrists, and after the honour of also being made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Physicians, he was invited to a meeting in Leningrad held by the World Psychiatric Association. There he heard about the way the Soviets were abusing psychiatry to lock up and ‘treat’ (assault) dissidents. When he got home he received clandestine reports from Russian dissidents, and organised “a couple of dozen leading psychiatrists in several countries” to begin a campaign to publicise and protest what was going on.

“That whole issue made me more aware of the thought-police function of psychiatry. One could easily see how deviance from the party line could get close to being called madness. It is but a short step for authorities who take exception to a person’s ideas to convince themselves that it is so bizarre to disagree with their own wisdom that the ideas must be clinically mad. This tendency should always be considered in any psychiatric work in any country.

It is interesting that international psychiatry does have a definition of delusion, which is that it is a belief held by less than six people. More than six people makes it a sub-culture. When leading psychiatrists define things like that there must be an element of coercive abuse. Some delusions are acceptable and some aren’t. And the ones that are acceptable are those held by people powerful enough to be a nuisance if you try to say they are mad.”

* * *

In 1978, under the impetus of the Italian political movement for Democratic Psychiatry, the big (and often horrific) old asylums in that country began to close down, so as to usher in a new era of community psychiatry in which patients would be listened to and allowed their freedom. Alec was very interested in what the Italians were doing.

When the UK followed suit (albeit, in a less radical or thoughtful manner) Alec came to look on closing down the big old mental hospitals and the movement towards community care as a definite overall benefit,

“…although more money would make it work a lot better. But, for example, the amount of violence from schizophrenics has not increased at all since community care was introduced. The newspapers like to give everybody the feeling that something dreadful has happened. The murder rate from schizophrenics is slightly higher than that of the general population, but not much, and we are all far more likely to be killed by a relative at home than by a random schizophrenic.”

All the same,

“My attitude is that it’s unrealistic to think that we could possibly deal with every instance without resorting to coercion. I’m not a dogmatic libertarian. I do think, however, that sectioning is quite often overdone. And not only is it overdone but also kept on for too long.

Of course the problem is that often the psychiatrist is frightened, and you can see why: he will be held responsible for whatever the patient might do. He has to protect his professional reputation as well as all the staff and public around the case. So the tendency is to err on the side of safety rather than risk.

The language we use, too, can be very treacherous. The words ‘psychosis’ and ‘schizophrenia’ appear to represent clear things when really they are just fairly useful with a sort of halo, diffuse meaning. I don’t take the view that those words have no meaning. I have a great respect for the early workers in the field who used such terms as they struggled to define the problems. But you can only approach matters with the terms you’ve got, and from the ideological context which you inhabit. I think the categories are semblances, descriptions of real events.

We ought to be running a type of psychiatry which is aware of our ignorance rather than one which is confident in its answers….

As my career progressed, I looked less and less to the category ‘madness’ or to how people were mad, but more to what was driving them mad. I became increasingly committed to understanding the person in humanistic terms. When I was younger I was all for explaining but as I got older I was all for understanding. In order to grasp what it’s like to be the patient a life history must be ascertained. I think you have to accept that an understanding is always more precarious than any natural scientific explanation. You can’t measure understanding statistically, as you can measure bacteriological processes. But understanding is the most relevant process for human activity.”

* * *

“I would say that things have got continually better in psychiatry throughout my career. When I first went into psychiatry the beds were side by side on huge wards, people didn’t have their own clothes, there was crowding. The whole place suddenly became quiet when the phenothiazines came in, the shouting stopped and you could hear yourself think. They also gave a sense of enthusiasm, the feeling that at last something could really be done. There was no hope in psychiatry until just before World War I. The great authorities who wrote about mental illness had no reason for optimism until GPI began to be cured. The optimism that arrived with the phenothiazines, in mid-20th century, led people to believe that psychiatric wards could be reduced to just a rump attached to the general hospitals. This was a bit misplaced, but still, things did improve dramatically.

Relations between doctors, nurses and the other professions have changed so much for the better. When I started, the nurses stood to attention next to the bed with the patient when I did the rounds, seeing hundreds of people… Things have become far more democratic as between the various psychiatric professions. I favour that. Still, efficient decision-making demands some sort of hierarchy of responsibility because there has to be a desk at which the buck stops. What is needed is a balance.

There have been noticeable differences in the types and proportions of presenting psychiatric conditions over the last fifty years. When I came into the field you would see a lot of posturing catatonic patients… This has disappeared. It’s made a fantastic difference. In 1913, Kraepelin reckoned that 10% of all presenting cases were catatonic. And yet now I should think most doctors, even psychiatrists, would never have seen a case.

I came to believe that that sort of catatonia was partly a product of the hospital. Catatonia is a final stage of impasse. It was really the end of the road when a patient reached a back ward of one of the old hospitals. Catatonia doesn’t occur if you give people phenothiazines. Most people who get to a General Practitioner will get something or other and not reach that end-state.

Schizophrenia, in general, is not as wild as it used to be, and hysteria is not as gross. Hysterical blindness or deafness or lameness, or aphasia (inability to speak) all seem to have abated. The grossness of the psychiatric conditions seems to have lessened. This change is due to the fact that nobody is left to get so bad any more, at least anywhere where there are modern psychiatric facilities. Consequently anxiety and depression have become the more common forms of problems, and they are of course rather less spectacular forms of malaise.

The psychiatric system became a lot more liberal during the last half of the 20th century. The ‘revolving door’ intake of patients has replaced the old sort of terminal hospitalisation. People are having much longer periods outside. I’m quite optimistic about the progress that has been made in psychiatry during my time. It all comes about through the constant pressure of various interest groups, but positive things have been achieved through people pushing for changes. The more educated people become about psychiatry the better they can negotiate with the hierarchy which used to concentrate nearly all power into its own hands.

When I first started as a junior psychiatrist, I had 500 patients. When I was appointed professor I was the only one in the Trent region – which took in about an eighth of the UK’s population. Now power has been spread to all sorts of places and there are half a dozen professors of psychiatry in Sheffield alone. And the other psychiatric professions and MIND and patients’ groups have all taken bites out of that once nearly absolute power.

So far as treatment goes, the big change of course was the introduction of the new drugs. I also came to the conclusion that in a limited way ECT does work, but only in very special circumstances. Of course there have been campaigns against its use and it is given far less often now. I didn’t use it once in the last five years of my clinical practice, because I didn’t feel it was needed. I avoided it like the plague because I thought it was a very crude solution to a human problem.

I do not think ECT should be rushed into. When I began in psychiatry ECT would be given routinely, and if it didn’t work – then we would speak to the patient! Its use has been moderated, but I do think it’s still far too much over-used. But I was opposed to a total ban. During the last five years when I didn’t use it at all, one woman was in a dreadful state and all the staff wanted her to be given ECT. They said I was just letting my ideology stand in the way of treating the lady. So, democratically, it was agreed that she should be given ECT. But she couldn’t sign the forms and her relations wouldn’t sign them, so we had to wait to get a second opinion from outside Sheffield. That was going to take a week or so. The day before the other psychiatrist was due to arrive she suddenly got better!

This also illustrates the great difficulty in making confident decisions. I strongly advise humility in the face of psychiatric disorder.”

* * *

“I’m much in favour of patients’ self-help groups and advocacy, which has really come along in the last [thirty] years or so. But I have come to the conclusion, having been involved with a little drop-in centre that patients run for themselves, that there is something a little unrealistic about thinking that people who are very disturbed are the ideal agents to take total control. It’s a bit of a contradiction in terms. Such people are not necessarily all kindness to each other just because they share a fate. They shouldn’t be romanticised. The place tends to be bedevilled by a massive use of drugs. This is against the rules of the set-up, but it’s very difficult to stop people buying and selling there.

There has been a tremendous increase in drug abuse during my career. When I was a student, a heroin or opium addict would be an unusual case. Not now. What is interesting is that laudanum and opium were widely used at the end of the 19th century yet they disappeared at the beginning of the First World War. The problem just ceased to exist from about 1910 until the 1960s and the Vietnam War…

Currently there is a big and growing problem of psychiatric drug-dependency. I’m for the total legalisation of all drugs. Alcohol seems to be more trouble than it’s worth – the Muslims are probably right about that. I don’t think the police and prisons can really deal with the huge problems posed by completely outlawing certain drugs.

I think the fear of madness is really due to a concretised view of what madness is. It is frightening to contemplate the loss of your reason, but most people’s ideas about it are not very realistic. I think psychiatric workers, dealing with it day in and day out, become a little indifferent to the generalised societal fear of madness.

I believe that psychiatric care or help should be based on intelligence and humility. We are dealing with things that are far more complex than we can comprehend. But we have to deal with them. Usually we can deal with it best by assuming that the person who confronts us is more like us than not like us. The psychiatric patient is not from outer space. So the best thing to do is the thing to which you yourself would respond most favourably.”

* * *

Research reports and comments by Alec were published in various academic journals, and he wrote articles for Asylum magazine. But his only book – a collaborative project, of course – was on schizophrenia. It seems he only found time to work on it when he had retired. The title indicates what Alec had come to believe. Jenner, FA et al (1993) Schizophrenia: A disease or some ways of being human? Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

Apart from arguing for a ‘humanistic’, psychodynamic view of the nature, causes and treatment of psychosis, the book has chapters which review the neurobiological and genetic schizophrenia research. There he thoroughly debunks the consistently faulty evidence and arguments of the psychiatric orthodoxy which, against all reason and science, insists on the truth of the medical model of mental illness. In the meantime nothing in the field of psychiatric research has fundamentally changed, and Alec’s argument is well worth reading. Remember, he knew what he was talking about – very few of his peers, if any, could claim a genuine working knowledge of biochemistry, statistics and genetics, as well as psychiatry.

Alec’s book is given detailed consideration, and his analysis of the neurobiology and genetics research is condensed into an appendix, in: Virden, P, Jenner, FA, & Bigwood, L (2008) Psychiatry: The alternative textbook. Asylum Books/Tiger Papers. (Revised edition soon to be published). Alec’s words (above) are from an interview which constitutes Chapter 8 of that book.

Phil Virden, Executive Editor Asylum magazine