“Turn Illness into a Weapon” professed the manifesto of the SPK or Socialist Patients Collective. “The kidney stones that make you suffer,” they declared, are the same as “the stone thrown into the control room of capitalism. 1

Published in 1972 by a group of patients, doctors, and students at Heidelberg University in West Germany, the SPK’s manifesto took aim at the ways mental illness is reduced to a personal issue — asserting that it is impossible to separate any one person’s mental health from the wider ills of capitalist relations 2. To heal any one patient they proclaimed, the patients would have to heal the system itself.

The problem with the current system of mental health care under capitalism is its iatrogenic nature — meaning the supports put in place to treat our afflictions have the effect of worsening them. For example, the suffering of anxiety does not emanate strictly from the condition of anxiousness, it is also an aggregate of stigmatisation by other people and surrounding biomedical, social, and economic structures. Through the language of resilience, people’s feelings of empowerment are constantly transformed (weaponised) into a burden of self-reliance (i.e. fitness for work) that falls squarely on the sick person.

The primary directive of the mental health professions is to return sufferers to a state of ‘normality’ by placing rigid limits on what constitutes healthy and constructive behaviours. These limits often appear as false dichotomies between health and sickness, productive and lazy, wanted and discarded, which are so powerful it seems like the only habitable space is at one pole or the other. This leaves no place to exist in the contradictions that colour sickness and normality. Either you are happy and ‘have’ mental health, or you are unhappy and therefore ‘have’ some internal deficiency or chemical imbalance.

And yet, considering the very real and pervasive anxieties the past few years have enlivened, people are asking whether their failures to uphold impossible standards, rather than being a personal problem are in fact a wider failing of an iatrogenic system that can no longer obscure its disparaging logics. Rates of anxiety climbed by more than 25% in 2020, a devastating ripple effect of compounding economic, ecological, and pandemic crises that have disproportionally affected marginalised people around the world. That is tens of millions more cases of anxiety, in addition to the nearly one billion already occurring.

Integrating anti-psychiatry with patient-focused praxis, the SPK argued that ‘healing the system’ requires fashioning a political therapy that re-frame illness as a basic contradiction created by capitalism, which could, under certain circumstances, be embraced to bring an end to the system that gave it life. They argued that those categorised as ‘ill’ or ‘unwell’ can be mobilised as an alienated underclass united in their shared suffering. Since mental health has the advantage of being familiar to all, anyone can be a potential provocateur so long as they disavow the personalised nature of their problems.

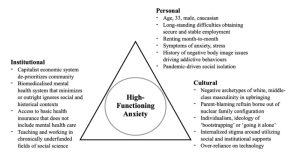

By advancing a holistic framework, that situates individuals’ problems within their full matrix of personal, structural, institutional, and ideological determinants, new forms of health modelling can help to visualise problems in their totality as the SPK intended. Using the liberation health triangle illustrated below, we can see how each point signifies the different factors contributing to mental distress. 3

Centering my own struggles with high-functioning anxiety, the triangle is a helpful tool for linking institutional (lack of access to mental health care in a chronically underfunded capitalist system); cultural (internalised shame and stigma based in ideology of self-reliance); and personal (negative body image, isolation, and stress) issues.

Cultivating an analysis like this is a distinct departure from the problem-story offered by mental health professionals. Instead of reducing the problem of anxiety to negative behaviours resulting from the stigma of personal failings, the chief agents of discord become a lack of comprehensive health insurance, unstable housing and a job market that engenders precarity and disposability. Based on this realisation, I can move from a subjugated ‘object’ position, paralysed by my own faulty wiring, to an activated subject position empowered to renegotiate the story of my anxiety in the context of overarching social structures, assumptions, and beliefs.

By recognising how mental illnesses are structured in larger contexts like this, people can start to ‘make sense’ of their personal feelings of psychic and political oppression – calling into question the status quo in solidarity with other oppressed groups. The point is not simply to recount pain and suffering but to restructure and transform it.

Turning anxiety into a weapon is not about cohering around a single shared identity. Nor is it about flattening different lived experiences of mental health. Rather, it is about the collective enunciation of shared interests, in the face of precarity, by forging concrete understandings of the material conditions through which our anxieties are produced.

Footnotes:

- Socialist Patients’ Collective (SPK), Turn illness into a Weapon: a Poelmic and Call to Action by the Socialist Patients’ Collective of the University of Heidelberg (Munich: TriKont-Verlag, 1972).

- For a detailed history of the SPK, see: Helen Spandler, ‘To Make an Army out of Illness: History of the Socialist Patients’ Collective’ (SPK), Heidelberg 1970/72. Asylum: The Magazine for Democratic Psychiatry, 6, no.4 (1992)

- Dawn Belkin Martinez & Ann Fleck-Henderson (Eds). Social Justice in Clinical Practice: A Liberation Health Framework for Social Work (New York: Routledge, 2014).

A.T. Kingsmith is a researcher, technologist, and author. He teaches the political economy of mental health at the Ontario College of Art and Design. For more of his work see www.atkingsmith.com.

This is a sample article from the Summer 2022 issue of Asylum (29.2). Subscribe to Asylum magazine.