I’ve known for a long time that being an NHS mental health nurse from the 1970s to the 2000s has seriously affected my own mental health.

This account is my attempt to make sense of how this happened. In some respects, this might be similar to service user accounts of how their experience of mental health services has affected them, and while I was in a different power position in the system, I can’t help feeling that the solutions are the same for us all.

When I was 18 years old, in the early 1970s, a relative who was a charge nurse at the local psychiatric hospital suggested I take a summer job there as a nursing assistant with accommodation thrown in. The interview was cursory and I started the next week. It was a shock being thrown into a closed world of people with very strange behaviour and of paternalistic staff who believed that they were doing what was needed. The hospital used to be called the County No 1 Lunatic Asylum and was located by the Victorians in splendid country isolation. This very isolation helped me transition from my family schooldays into this encapsulated and rigidly demarked community, with me at the bottom of the staff hierarchy.

When I started, the hospital was primly split into male and female halves and there was a powerful culture of boasting masculinity amongst the male staff, casually denigrating women and neurotically hostile to homosexuality, with a barely concealed undercurrent of porn everywhere. Paradoxically, there was a thriving hidden staff scene of male with male casual sex. But woe betide any resident forming anything that might resemble a sexual relationship with anyone else. I remember one instance of a male resident having the temerity to announce his engagement to a female resident. He was immediately segregated and treated with female hormones, with extremely painful side effects. It took me a long time to understand the corrosive effect all this had on my own immature sexuality and intimacy needs, causing me problems that continue to this day.

Before long I realised that some staff enforced this culture with a degree of covert violence, not only towards some of the more disturbed residents, but also towards staff who criticised this situation. And at that time most white staff were openly racist towards the growing number of Asian doctors and African nursing staff. The hospital was totally dependent on them to keep staffing levels up, but they were denied promotion and casual insults were their daily experience. As a white man I tried to speak up for some of my black colleagues, and thereafter was cold shouldered by many white staff. All this was known about by the more senior managers, who looked away and took no action. Surviving the Mental Health System – a retired staff member’s view.

Despite all this, there were a few inspirational nurses who bucked the trend and inspired me to train as a nurse. However, student nurse training back then reflected the worst aspects of an apprenticeship, devoid of any teaching of psychology or therapeutic skills. On qualification I felt that I could run a ward and manage medication but not talk to patients.

During my training I came across a book called Asylums by Erving Goffman, a well-respected American sociologist. It dissected the social relationships and rules of the closed space of personal interactions in mental health hospitals at the time. It laid out the idea of ‘institutionalisation’, the process where people denied rights in a closed institution lost their volition and became habituated to the routine, to the point where they were dependent on it. And while staff are more privileged than patients in this system, many of them were, too, made dependant of the routine of the place. The book rang so very true for me in England, but I was astonished to be told by our nursing tutor that I should not read it until I had finished training!

Five years after I left the hospital, I went back for a nursing conference and found the same staff and patients in the same queues in the same corridors. This made me realise just how institutionalised I’d been there, as I’d had to leave the place before I noticed it.

After qualifying, I worked in several other psychiatric hospitals as a staff nurse, each with a similar culture of a casual lack of compassion and skilled mental health care. In the late 1980s I became a charge nurse in a university town hospital which had a more aware and permissive culture. There I began to learn some of the skills and knowledge that my nursing training should have supplied me with earlier. However, just when I was rediscovering the true meaning of the word ‘asylum’, as a safe, caring and healing place to retreat to, there was pressure to close the hospital to save money. We were expected to place our long-term residents in nursing homes, bedsits and community homes, risking a new level of neglect.

I was split between wanting these old buildings and their terrible history to be swept away, and fearing what would replace them. Like many of my peers in the early 1990s, I became a community psychiatric nurse (with no further training!) and found myself managing many people with long-term mental health conditions in the community. The only real therapy that was being offered at this time was psychotropic medication – mainly major tranquilisers, made respectable by being called ‘antipsychotics’ by their manufacturers – which did seem to make many of our service users more ‘manageable’ but equally seemed to turn them into emotionally-flattened asylum summer 2023 page 11 zombies. We should always remember that we still do not fully understand exactly how these drugs work, despite the hype.

Another inspirational colleague encouraged me to work collaboratively with service users: to see them as the ‘experts’ on which medications worked for them and when, urging me not to feel that we must treat symptoms of ‘psychosis’ if they weren’t distressing or maladaptive. It was not easy to make the three-way alliance between nurses, prescribers and service users work, especially with the background threat of the Mental Health Act to compel some to accept treatment. We also had to deal with a popular press narrative at that time of ‘the loonies’ and the staff who can’t control them.

Many of the people I saw had also experienced the hostility of the benefits and housing systems. Learning from a social worker with benefits expertise, I helped many service users get the benefits they were entitled to. It was probably the most effective nursing care I offered many of my clients in terms of alleviating distress and being able to afford some dignity in their lives, though my line manager discouraged this as ‘not nursing’, despite paying lip service to ‘holistic’ care.

I was also expected to work in a counselling role with many people who were in crisis with anxiety or depression, occasionally offering targeted anxiety management therapies, without any formal training. In retrospect, I am appalled by the way we just learnt ‘on the job’. To create a safe enough space for clients to take risks and change, the counsellor needs their own support, as they bring both the gifts and foibles of their own personalities to the job. Despite managers talking a lot about ‘supervision’, I found it was used more as a mechanism to ensure we offered as few sessions to patients as possible, and quickly discharged them to save money, rather than supporting staff. With hindsight, I believe that I occasionally started to meet my own needs for psychological intimacy through these counselling relationships, rather than enabling clients. Perhaps it is unsurprising that proportionately more male than female mental health staff end up in disciplinary situations given how they are generally ill-prepared for this sort of emotional labour.

By 2005 I felt unable to cope, thinking I had seriously failed several of my clients. I started to drink, leading to sickness absences. Some colleagues were supportive and understanding of my state, but powerless to help. Early retirement was a sort of rescue, but with periods of guilt-laden depression, leading to my own (elective) use of antidepressants and counselling to make sense of it all.

In summary, our NHS mental health system took a raw young man as a willing worker but failed to help him learn to safely help others through their mental distress. I was brutalised by institutional care, then quite unprepared for the intimacy of the therapeutic relationship when providing care in the community.

My manifesto for change would include:

• Funding well-trained and supported staff and providing a wide diversity of talking and social therapies, including addressing economic hardship.

• Actively enabling all service users to freely decide which therapies and social support suit them, including medication.

• Accepting that this work can exact a serious toll on staff, who also need support.

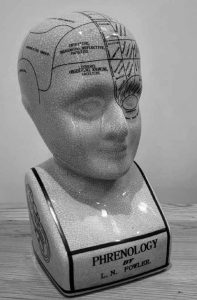

Perhaps I should not have been a mental health nurse, and this is just a long excuse for my failings. But when you consider the ideal attributes of such a person, I think it’s hard to find people who fit the bill. I still believe that we can all change for the better – both those in a helping role and those seeking help – if the right conditions are created for this to happen. I have a reproduction phrenology head as a reminder of once sincerely-held beliefs that are now superseded. It is a hopeful object, representing progress. That is what I want to contribute to here.

This is a Sample Article from the Summer 2023 issue of Asylum Magazine. Subscribe to Asylum.