I recently requested the past several years’ worth of my medical records from mental health services.

I needed supporting evidence for my upcoming Personal Independent Payment (PIP) review. Having requested 8 years’ worth of notes a few years ago, I was aware they would likely be a devastating read. Perhaps even traumatising. What I was not expecting, however, was to discover a running theme throughout everything professionals had documented over the past few years.

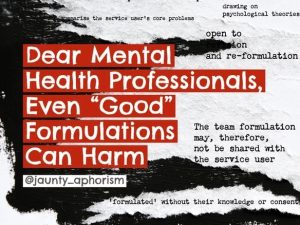

For several years with community mental health services, I was under the care of a psychiatrist and clinical psychologist who were critical of traditional psychiatric views and the medical model of mental illness. In general, they believed themselves to be practising some form of “trauma-informed” care which was anti-diagnosis, anti-medication, and anti-psychiatric-intervention. I found numerous aspects of their methods difficult to cope with, including the refusal to allow me to have the specific therapy of my choice, and the removal of my longstanding PTSD diagnosis in exchange for a non-consensual psychological ‘formulation’. Along with countless inaccuracies, misrepresentations, and fictions within this formulation, the clinicians also included intensely private and humiliating details of my childhood abuse.

Deeply unhappy with how I was being treated by the community mental health team, I had requested two things. Firstly, a referral to an independent trauma and dissociation service, so I could be seen by a specialist, and secondly, to have my PTSD diagnosis back, so that I would be able to request support from organisations such as the DWP (Department of Work and Pensions), the local council and my university, without revealing all the deeply personal and private details of my trauma which lay in my formulation.

My notes revealed that the clinicians somehow concluded, from these requests, that I had a desperate desire for a diagnosis, and due to their world-view, that diagnosis was inherently negative and unhelpful, they interpreted this as a sign that there was something wrong with me. They mentioned my previous request to have an autism assessment (which I had subsequently undergone and been diagnosed autistic) as proof that I just couldn’t stop seeking diagnoses. I was a pathological diagnosis-seeking machine.

The impact this had on subsequent care was dramatic and can be seen rolling over and over in my notes throughout the next couple of years. Despite this alleged behaviour first having been recorded by an anti-diagnosis clinician, and not being present in any other area of my mental or physical healthcare notes, other professionals started framing everything I said and did as “diagnosis seeking”. Even professionals who were not ideologically opposed to diagnosis seemed to take my notes as gospel and concluded that I did indeed have a pathological need to be diagnosed, even when our interactions didn’t once mention the topic.

For example, the psychiatrist with the early intervention in psychosis team (EIP) wrote repeatedly that I was clearly seeking a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (simply by attending an assessment). The EIP multi-disciplinary team concluded from my initial assessment that, due to the nature and severity of my symptoms, they “had no choice but to accept me” into their service, but they must be extremely “boundaried” in their approach and not convey in any way that I was going to receive a diagnosis of any kind of psychotic disorder. A nurse with the street triage team, who I was forced to speak with by the police during a recent crisis, concluded that the reason I did not want any interaction with services was not because I had been so traumatised by them that I couldn’t cope with further contact (as I explained to her), but because I was upset no-one would diagnose me. She then bizarrely reinterpreted my GP referring me to an independent provider of NHS services for trauma and dissociation, as me going round private psychiatrists looking to be diagnosed with a dissociative disorder.

What struck me about all these notes was that at no point during those few years did any mental health professional indicate they thought I was pretending to be unwell to seek a diagnosis. They did not believe I was making up symptoms. Nobody once said, “Wren thinks she has X-disorder but does not meet diagnostic criteria”. The notes conveyed no disbelief whatsoever in my presenting symptoms and mental state, and in fact concluded that I met the criteria for acceptance into their service. As such, the repeated insistence that staff must withhold a diagnosis from me appeared to be entirely punitive, based on their belief that I really wanted to be diagnosed, and as such, should not be. I was having a diagnosis withheld because, by challenging my psychiatrist all those years ago, I had inadvertently engaged mental health professionals in a power struggle… and, as the patient, there is no way I could be allowed to win.

I have since discharged myself from all NHS mental health services, and as such have, no route by which I can express myself to these clinicians. So, I shall say it here: If you do not understand the necessity, as a disabled person in today’s society, of having a diagnosis then you are exceptionally privileged. If you do not understand how distressing it is, as a trauma survivor, to be forced to share intimate details of the horrors in your past, in a formulation you didn’t even write, then you are not ‘trauma-informed’.

I do not want to drape myself in diagnoses, I have no pathological desire to be labelled or shoved in boxes. What I asked for (which was actually a tiny request, in a sea of interactions with services) was a mental health diagnosis which encapsulated my difficulties, so that I could share this with other services when I required support. These included the DWP, the local council, my GP and my university.

As a clinician, you may personally be ideologically opposed to diagnosis, but the world has not caught up with you. Systems designed to help are often only accessible with a diagnosis. Not just systems, but also other medical professionals. Trying to explain your health needs to someone like a GP routinely leads to the question of your diagnosis. When you tell them you don’t have a diagnosis, the assumption is that you are undiagnosable because there’s nothing wrong with you, and as such, you don’t need any support. The whole world assumes that if you have a problem, you will also have a diagnosis, so when you show up with a formulation which lays out all the details of the trauma you have experienced, but includes no medical description of your problem, you are turned away.

This is the reality. Denying that reality, and pathologising people who request a diagnosis rather than formulation feels deliberately cruel and obstructive. It goes directly to the heart of my issue with the critical psychology/psychiatry, anti-diagnosis movement. Just like the medical model; if we as patients don’t agree with you, we are punished, pathologised and ridiculed.

In my view, the problem with current mental health services, is not that patients are being diagnosed with a mental illness and prescribed medication, it’s that we are systematically stripped of power. We are given no choice in who we see, where and when we see them, how long we are seen for, what therapies or what treatments we access. We have no control over what is written about us, how we are conceptualised, what language is used to describe us, how our information is stored, and who accesses that information.

We have no right to direct our own care and no authority to decide what is or is not “wrong” with us. We have no power to present our experiences as truth, and no means by which we can dispel the suspicion and contempt we are treated with. We have every inch of our humanity taken from us, and if we display even the slightest hint of discomfort, we are punished, pathologised, discharged, dismissed, re-diagnosed, or re-formulated.

This is not unique to professionals who espouse the medical model. All this was done to me in the name of my apparent liberation from the medical model, and that’s the problem. Critical approaches to mental health care, including ‘trauma-informed care’ and anti-diagnostic interventions are not new, radical, or better than the medical model if they continue to work within the same power structure: one in which the professional is still always right and in control.

Unless there is a fundamental shift in the power dynamic between us and “professionals”, nothing will ever change. And, quite honestly, nothing I have seen or experienced from “critical” practitioners, either online or in real life, gives me any reason to believe that, as a group, they are willing to relinquish that power.

You can find more of Wren’s writing on her blog: www.psychiatryisdrivingmemad.co.uk/

This is a Sample Article from the Winter 2022 issue of Asylum (29.4). Subscribe to Asylum magazine.